After walking to Santiago de Compostela for the first time in July 2024, I caught the Camino bug. No, not bed bugs, but rather I couldn’t wait to start planning the next one. Like many good pilgrims before me, I fell in love with the simpleness of waking up and walking all day, every day. There’s just something special about feeling like a part of nature and being amidst the trees and watching butterflies and dragonflies flit through the air. I knew I wanted to come back and walk another route to Santiago de Compostela sometime in the future. However, I didn’t expect to be on the trail again just a few months later, following yellow arrows on the Camino Portuguese. I found myself in Portugal with two weeks to spare and thought, why not?

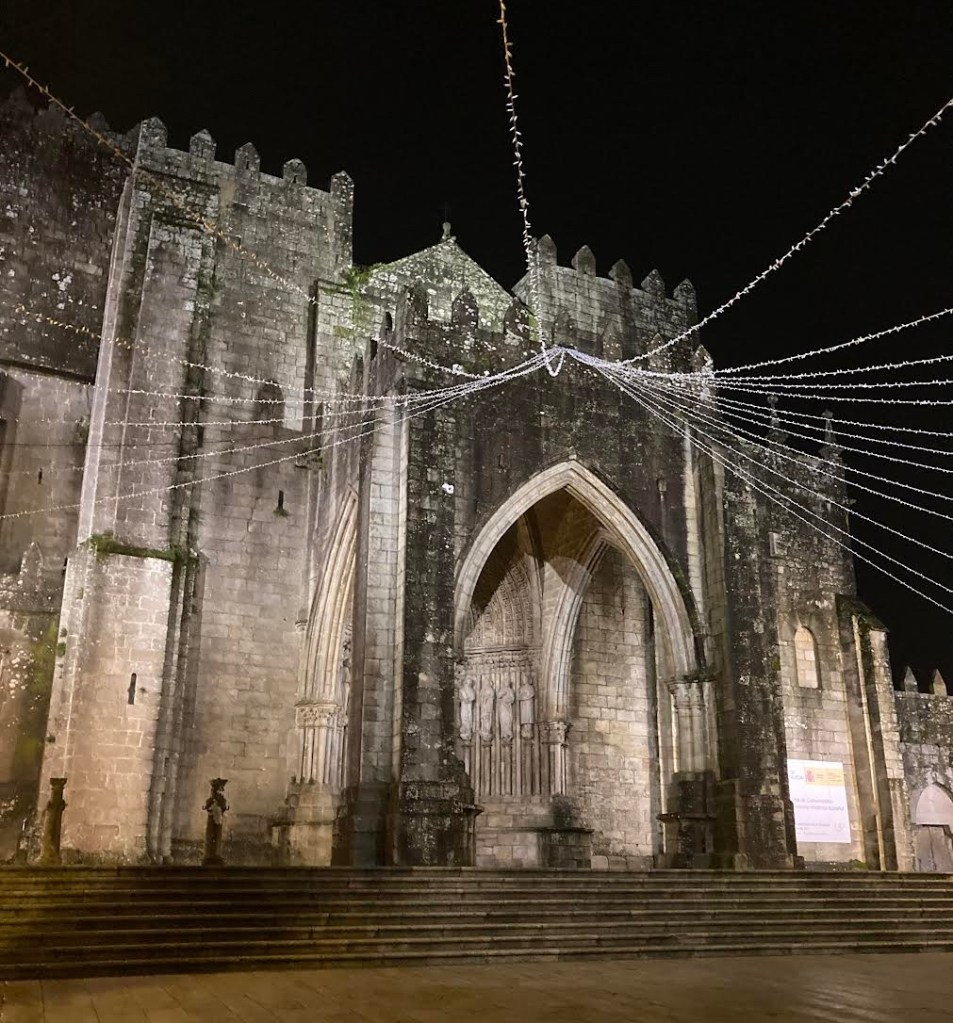

This time, it would be November instead of July, rainwear instead of shorts, and hot chocolate instead of ice cream. The air had a certain crispness to it, especially at night, and dusk came earlier every day as I arrived in towns lit up by Christmas decorations. While I still met pilgrims on the trail most days, especially in the last 100 kilometers of walking, the crowds were small compared to the amount of people on the Norte in summer.

With emptier albergues and seasonal closures, walking a Camino in winter can be a reflective experience that’s ideal for going inward. Here is everything you need to know about walking the Camino Portuguese in the winter months, along with some personal musings and insights I took from the experience.

The Portuguese Camino, By the Numbers

With almost 89,000 people walking the Portuguese Camino in 2023, it has become the second most popular route after the Frances. Some pilgrims choose to start their walk in Lisbon, which is 620 km from Santiago. However, Porto is the starting point of choice for most, and from here you can begin either the Coastal or Central route to Santiago.

As the name suggests, the Coastal route follows the coastline out of Porto, winding through charming towns and scenic beaches. Eventually it merges with the Central route in Redondela, Spain, although there are multiple options to cross from the Coastal to the Central along the way. In total, the route is about 274 km and takes about 12-15 days. It doesn’t have much elevation gain, so if you’re not a fan of hills, it might be the Camino for you.

The Central is an inland route that leads through forest paths and several historical towns, such as Ponte de Lima, with a distance of around 244 km. There are some more strenuous climbs on the Central route compared to the Coastal, although the hills don’t get too crazy. It takes about 10-14 days, depending on how you break the stages up. Including the Spiritual Variant, it took me 10 days to arrive in Santiago, but you can definitely go at a more leisurely pace if you want to take more time.

I chose to walk the Central route this time, as I thought weather on the coast might be a little bit more unpredictable in November (hello wind) and I was looking for a change of pace from the Norte’s many beaches. After the routes merged, I did meet a few people who had walked the Coastal and they had nothing but good things to say.

Walking the Spiritual Variant

Near the end of the Portuguese Camino, heading out of a town called Pontevedra, there’s an option to take the Spiritual Variant (Variante Espiritual). This route, often referred to as La Translatio, reconnects back to the main Camino in Padron and is about 74 km in length. It takes about three days to complete in total, and the last stage includes a boat ride which retraces the route taken by the remains of St. James when they came to Spain. According to legend, the remains were brought by sea in a stone boat to the banks of Ria de Arousa. From there, they were carried to the area now known as Santiago de Compostela.

Although it’s a bit longer than the standard route from Pontevedra to Padron, I would really recommend walking the Spiritual Variant. It’s filled with natural beauty and bypasses industrial areas and busy roads. There are fewer pilgrims on this route, especially in November, but it was peaceful and a nice change of pace.

The first day (Pontevedra to Armenteira) includes highlights like the monastery of Poio, a historic coastal town called Combarro, and a steep uphill forest climb to Armenteira, where there’s another monastery worth exploring. In the winding alleys of Combarro, many of the little squares contain historic stone crosses. I was fascinated to learn that these were erected in areas of the town associated with witchcraft and Paganism. The crosses were meant to put a stop to these practices. While the day’s distance is relatively short at 21 km, I was quite tired when I arrived at the municipal albergue in Armenteira, where I was the only pilgrim staying for the night.

The second day is one of the most beautiful days I’ve spent on any Camino so far. It begins in a magical forest along the Route of Rock and Water (Ruta de Pedra e da Agua). The riverside path takes you past mossy boulders, lush green foliage, and the stone remains of old mills. From there, you’ll pass through some quiet towns until you reach the pretty coastal path that leads to Vilanova de Arousa. The gentle day is around 23 km in length.

Before turning in for the night in Vilanova de Arousa, take a mental note of the big yellow arrow pointing to a glass building and pier. This is where the pilgrims’ boats to Pontecesures leave each morning at 8am. One thing to keep in mind if you’re walking this route during the winter months is that the boats won’t sail unless there are at least eight passengers. In the summer, they’re typically full, so you may need to purchase tickets online in advance. However, in the winter, you have the opposite problem. Luckily, there was a large tour group when I arrived at the dock in the morning and we got on the water bright and early. It’s also possible to walk to Pontecesures as a one-day stage along the water if the boat doesn’t run on the day you’re there.

The boat ride itself takes about 1 hour and 30 minutes and continues along the River Ulla, stopping along the way at stone crosses and other monuments. Personally, I wasn’t the biggest fan of the ride, although many say it’s a highlight of the Spiritual Variant. I just don’t like cold early mornings on boats, and the ride cost 25 EUR, which seemed a bit excessive. A couple of short boat rides were also part of the Camino del Norte, but they were about 2.50 EUR in comparison. Sigh. Once you get off the boat, it’s about 30 minutes walking to Padron, where you can either take a rest day or continue the 24 km to Santiago if you’re feeling the energy.

A Winter vs Summer Camino

If you’ve walked the Camino in warmer months and want to switch it up and try completing a route in the winter, here are a few main differences to keep in mind.

- Seasonal closures: First off, many businesses and albergues on the way close starting in October and can remain shut until March. This might mean you have to walk a little further than you intend on a given day or go longer stretches without a snack break. In November on the Portuguese, the closures weren’t too much to worry about and definitely shouldn’t dissuade you from walking. However, there was one long stretch to Rubiães where the only shop and coffee bar were closed. There were also a couple of closed albergues and some places that opened later in the day. It’s best to check the Gronze website ahead of time to stay up to date, as all operating dates and hours will be listed here.

- Emptier albergues: On the topic of albergues, you can also expect fewer crowds here. This was pretty nice, as there was no need to worry about booking ahead or racing to get the last bed in the municipal albergue. On the Norte in July, there were a couple of unpleasant surprises when I showed up to albergues after a long day of walking and they were all full. Although, I will say it was a little spooky being the only person in an albergue at night. Luckily, the Vákner didn’t show up and it was nice to fall asleep without the usual symphony of snores from neighboring bunks.

- Cold weather gear: This point is pretty self-explanatory, but if you’re walking in the winter, you’ll probably want to bring warm layers for those chilly mornings and evenings. I added a hat, gloves, rain jacket, and warm Patagonia jacket to my summer packing list and left the shorts at home. Most of the time it was fairly mild in terms of temperature, and there were even a couple of sunny, T-shirt weather days that I wasn’t expecting. The only day where it was a little miserably rainy and gray was when I arrived in Santiago. Can confirm that arriving to the cathedral in summer sunlight was more fun.

- Fewer pilgrims: Lastly, there are a smaller number of pilgrims walking the Camino in the winter compared to the summer months. There were a couple of stages where I saw no one, namely on the first day of the Spiritual Variant and before reaching Tui in Spain, which is where many start walking the last 100 km to Santiago. However, I still met kind and open people along the way, had some meaningful conversations, and saw that it’s possible to encounter some of that Camino magic any time of year.

Going Inward on the Portuguese Camino

Fewer crowds and noise does come with some advantages, namely that it’s easier to have a contemplative Camino and just be with your thoughts in nature. If you’re walking to process something or just find some peace and quiet, winter might be the best time for your Camino.

While on the Camino this November, a few themes and feelings rose to the surface for me. These are some of the main takeaways I hope to remember and share from the experience.

The Legend of Ponte de Lima

Ponte de Lima is known as the oldest town in Portugal, and it’s filled with charming medieval monuments. The most well-known of these is the bridge that crosses the river Lima. It’s composed of two sections, including the older Roman bridge that dates back to the 1st century and the newer medieval section from the 14th century. According to legend, when the Romans first arrived to the river, it was so beautiful that they thought it was the river Lethe. In Greek mythology, Lethe was one of the rivers of Hades’ underworld. Its beauty made anyone who crossed it forget everything, wiping away their previous life. The Romans didn’t want to cross the river, afraid they would lose their memories.

Walking into town, I was enchanted by the beautiful sight of a rainbow rising over the bridge. In that moment I could understand the Romans and their superstitions about this mystical river. However, as I sipped a matcha in town, the bridge in sight, I spent some time musing over the idea of forgetting everything and if I would want to do so. Like most people, I have my share of painful memories. Would it be a relief to let all the losses, the faces, the disappointments, and the tears go? To let them float away down the river as I held my breath and walked over the bridge, arriving on the other side a clean slate? For some moments, I was really tempted.

As I started walking toward the bridge, I realized that forgetting everything also entails saying goodbye to all of the good stuff. The love, the laughs, the magic, the days where everything feels right in the world. Sure, it’s cheesy, but I wouldn’t want to let go of all that I’ve learned from the experiences, negative and positive, in my life thus far.

I’m still wrestling with this idea after the Camino a little, in if what we learn from losing a loved one, for example, can somehow balance out the pain of not having them around. Does their loss help us understand that life is short and impermanent, and therefore encourage us to live more fully and compassionately? To take chances we otherwise might be too afraid to? Does it help us appreciate the good friends and people around us more? Of course, there should be no pressure to view loss positively, but thoughts like these give me some comfort when I’m missing my dad. I was able to walk the Camino on his birthday in July and the anniversary of the day he passed away in November, and have the time and space to remember him.

In the end, I held my breath and walked across Ponte de Lima, hoping to make it to the other side with my memories intact. The good and the bad.

Spotting Invasive Species

On a different note, a distinctive purple flower was my constant companion on the Portuguese Camino. Before starting the walk in Porto, I met an acquaintance at Terra Solta, a community garden by the Campanha train station. The volunteer-run garden, which was the only spot of green in a sea of gray concrete, was threatened by two things. Firstly, the train station wanted to expand, which would mean the garden would be paved over.

Secondly, there was a seemingly harmless-looking purple flower called ipomoea indica that was growing like wildfire around the perimeter. The volunteers pointed it out and mentioned how much of a pain it is to get rid of. The invasive species and weed spreads rapidly, climbing up trees and other plants in its path. It’s native to the southeastern United States, but has invaded Portugal, Australia, Kenya, and many other places. It strangles all plants in its path and when you try to remove it, the stems break.

Once on the Camino, I started noticing the purple flowers everywhere. Maybe it was because I was reading Harari’s 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, which discusses the impact of globalization generally, but I started thinking about how humans also act like invasive plants, arriving to a new place and spreading their culture to the point that it smothers and takes over local ways.

I kept asking myself the question, is globalization good? Perhaps in some ways yes, but I’m personally leaning more towards no. Over-tourism to the point that a place feels soulless and eroded (looking at you, Lagos, Portugal), permanent loss of culture and language, and wounded lands are just a few examples of globalization’s negative impact. There’s a lot more to unpack here, but this was the general theme I came back to while walking and spotting the innocent-looking purple flowers over and over again.

Headstand Practice

For the past few years, I’ve wanted to stand on my head in a straight line. Headstand is known as the king of all the yoga asanas and has great benefits, such as improved concentration and memory. For many people, it’s not that complicated of an asana, and they’re simply able to float their legs up after a little practice. However, for me, headstand has been a long-time goal with setbacks and frustrations, and I gave up on achieving it multiple times. There was the time I fell through a glass door and went to the emergency room for stitches, and then there was the time I booked a headstand workshop in a neighboring city, only to find out it was cancelled while traveling there on the train. I began to think that my body proportions just weren’t compatible with the pose.

Finally, finally, in the second half of 2024 I started to make real progress. I met some people who gave me useful tips and advice, and from there I started practicing on (mostly) flat grassy fields every day while walking the Camino. A big thing that helped my practice was getting over the fear of falling. I fell countless times on my back in the grass, but by rolling out of the fall like a ball I was able to get back up without any pain. Falling and wobbling are just part of the learning process, and they don’t mean you’re a failure or that something is impossible for you. I hope that this asana reminds me to always get back up and try again, in all aspects of life.

While I didn’t perfect the pose completely on the Camino, having the free time to practice in nature was really valuable, and I’m now able to hold a straight line. (OMG). Since headstand was so difficult for me to achieve, it’s a humbling and empowering pose to practice now. Plus, going upside down is really fun.

Leave a comment